Spring ushers in many gorgeous, fragrant flowers on plants native to the South Texas Sand Sheet. Once pollinated, the flowering plants, shrubs, and trees undergo a transformation right before our very eyes! Through the process of pollination, bees, butterflies, wasps, flies, and beetles, just to name a few, enable our native plants to produce marvelous fruit for wildlife! Another product of the pollination process are precious seed crops that are necessary for continuation of species.

The guajillo (Acacia berlandieri), which is in the legume family, is one of our native shrubs in the South Texas Sand Sheet ecoregion. The guajillo can grow upwards of ten (10) feet. Each Spring, it puts on a fantastic flower show with its tiny, white flowers sprinkled throughout its leaflet-covered gray branches. As with most plants in the South Texas Sand Sheet, the guajillo is armed with small, slightly curved thorns, which are called prickles. Its fruit is a reddish-brown legume, or seed pod, that is up to six (6) inches long. In each seed pod, there are numerous seeds that have the potential to become an adult Guajillo shrub.

As Spring marches forward, and after the seed pods have baked for just the right amount of time under the hot South Texas Sun, a prolific guajillo seed crop will be ready for harvest. Are you ready to harvest the seeds? Just kidding! You will not need to harvest these seeds, as they will harvest themselves. How is this possible? These seeds are disbursed by a ballistic (explosive) seed distribution method in which the heat from the sun dries the seed pods causing them to crack open with a violent force. The force of the explosion of the seed pod results in the seeds falling a bit farther away from the parent plant. Voila! Just add water, and the seeds on the ground are ready to grow!

During Springtime each year, I set about picking up seeds on a daily basis in order to save them for sharing with others. Each and every morning I will find brand new seeds that have been hurled out of their pods onto the ground. Should it happen to rain on the seeds before I get a chance to pick them up, I will have scores of newly sprouted guajillo seeds that are either still in their open seed pods or lying on top of the soil.

I have enjoyed a front row seat to the guajillo plant life cycle repeat, like clockwork, each Spring for the last couple of years. Consequently, I decided that there was no better time than the present to share this transformational process with others through photographs.

In my search for a simple outline of the life cycle of a plant as a starting point for this article, I encountered a plethora of sources and information. Some of these resources include life cycles that are quite detailed and elaborate. For the purposes of this article, I will simply state that the life cycle of a plant includes the following four (4) stages: Seed, sprout, seedling, and plant.

The following images of the guajillo plant life cycle were captured with my cell phone—a Galaxy Note10+. Other than placing them on a piece of cardboard covered with black felt to enhance their visual detail, the seeds, seed pods, and sprouts were not manipulated in any way. Additionally, the images were adjusted for sharpness, brightness, contrast, and saturation, using standard editing features that my cell phone came with.

Stage 1: Guajillo seed in the dried seed pod.

Stage 2: During germination, a sprout emerges from the guajillo seed.

Stage 3: This hardy guajillo sprout has matured into a seedling.

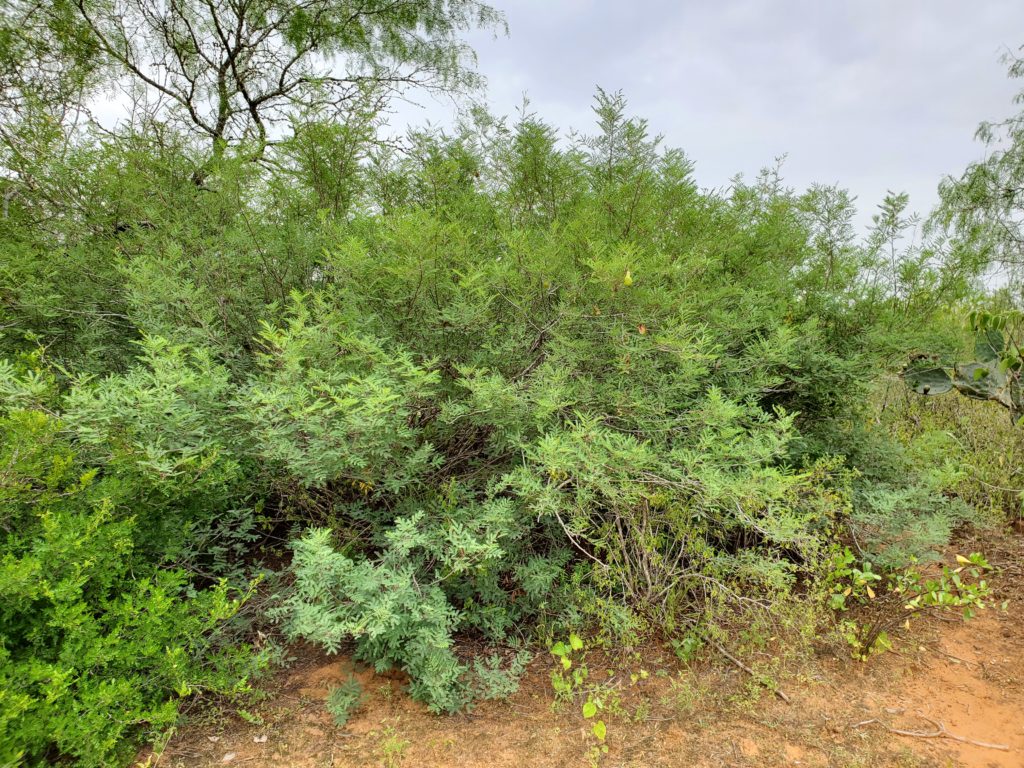

Stage 4: Young guajillo plant.

Additional information on the Guajillo:

In “Plants of Deep South Texas,” by Alfred Richardson and Ken King, page 239, we learn that “this is one of our earliest-blooming shurbs. It was named in honor of Jean Louis Berlandier, an early collector of plants from Mexico and Texas. Honey derived from guajillo is prized for its superior flavor. The leaves are toxic to livestock. They can cause what is called ‘guajillo wobbles’ and death. The plant is also recognized by the prickles, which are scattered around the stem rather than arranged in rows or pairs.”

In “A Photographic Guide to the Vegetation of the South Texas Sand Sheet,” by Dexter Peacock & Forrest S. Smith, page 191, we learn that “It can form in thickets on thin soils on higher-elevation sites of the Sand Sheet. The legumes produce dark brown seeds. Its leaves are browsed by white-tailed deer. It is a common component of tighter soils in South Texas.”